Rabies is preventable — but once symptoms begin, it is almost always fatal.

Rabies risk: what to do after a bite, scratch, or saliva exposure

Rabies is a viral infection transmitted through saliva from infected mammals. The decisive factor is timely post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and meticulous wound care.

Wash for 15 minutes

Start vaccine ASAP

Category III may need immunoglobulin

Travel hotspots: Bali, Thailand, India

Start here

If you are unsure: treat the exposure as urgent. Rabies PEP is time-sensitive and highly effective when started promptly.

Download the one-page PDF summary for offline use.

Download PDFCommon exposure scenarios

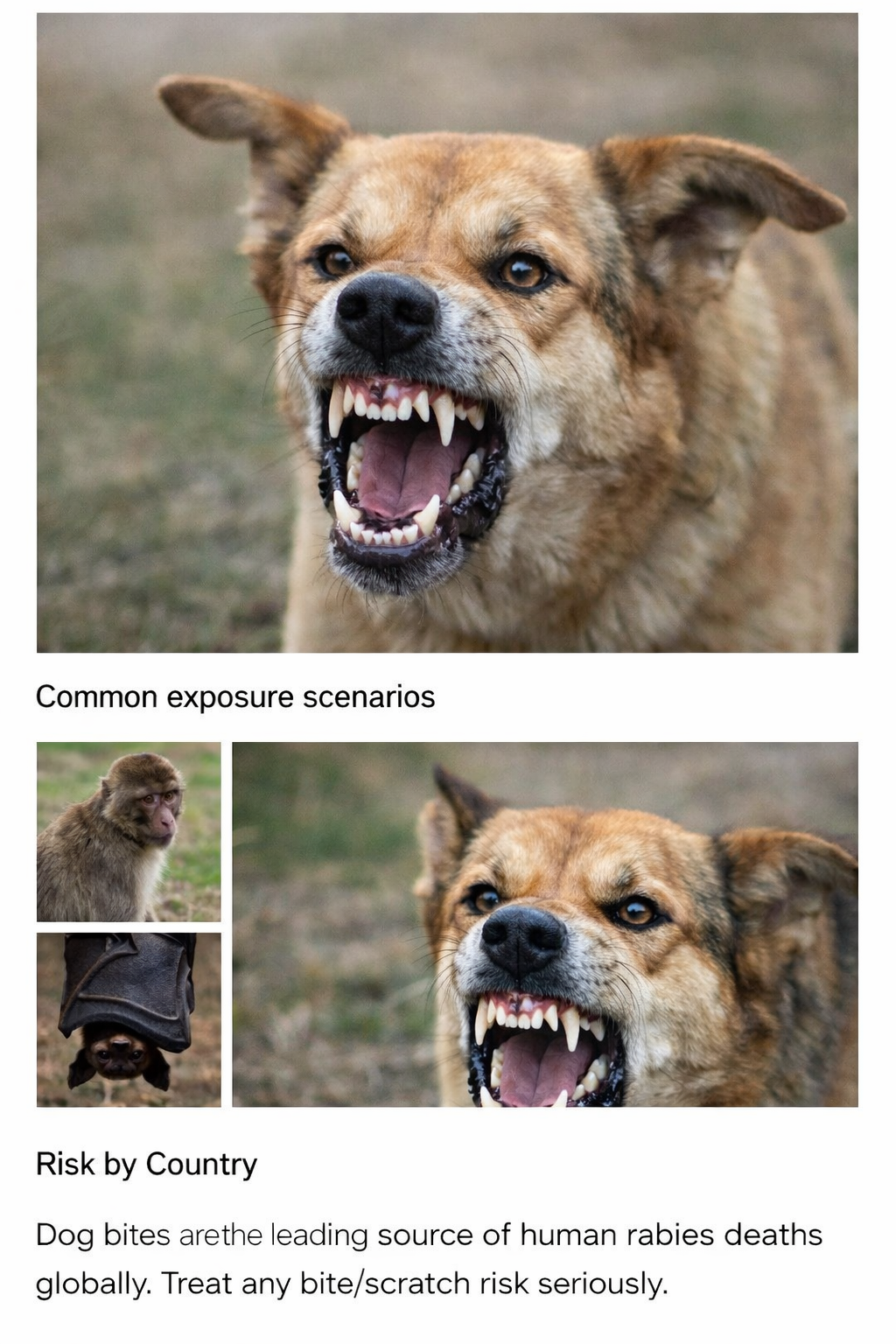

- Dog bite (most global human cases are dog-mediated)

- Cat bite or scratch (often underestimated)

- Monkey bite (tourist areas)

- Bat contact (even without a clear bite in some circumstances)

Why rabies is unique

Rabies can have a long and variable incubation period. The virus can travel via peripheral nerves toward the brain before symptoms appear.

Symptoms & outcomes

Once clinical rabies begins, outcomes are devastating, and mortality is close to 100% despite intensive care.

Travel and prevention

Pre-vaccination can simplify care after an exposure and is considered for higher-risk travel, long stays, or remote itineraries.